It’s not uncommon for brands to say its product stands for something more. This artful dinnerware is more than just a plate. Or this convenient tool is so much more than the name on its packaging. It’s also not uncommon for consumers to not quite understand what many of the brands actually mean beyond crafty marketing lingo. But with Kebaonish, an Indigenous- and woman-led tea and coffee company located on Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory in Ontario, the opposite is true.

How Kebaonish began

Co-founder, president and CEO Shyra Barberstock, who is Anishinaabe and a member of Kebaowek First Nation, first started planting the seeds for Kebaonish early on in the pandemic. For Barberstock, tea and coffee have always been “a hug in a mug.” It’s something she drinks when she is stressed out, wants to slow down or take time to connect with others.

Barberstock had been working in the service-based industry for a decade. Some introspection she did during this time made her realize a couple of things. She wanted to add a new challenge to her resumé by working in the product space. And she really missed the sense of community she felt when she shared a cup of coffee or tea with someone else.

“I started to think about things like storytelling and connection,” she says. “I bet there are so many memories that you have where you had this amazing story to tell somebody and you went ‘We need to go for coffee.’ We always tell our best stories over coffee and tea.”

So, Barberstock wondered, what if she could create a brand that brought that connection back into people’s lives? She started talking about this idea with her husband, Rye Barberstock (who is Haudenosaunee and a member of Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte). She also spoke to friend entrepreneur/consultant Barry Hillier, designer Michael Carrick and tea-industry pro John Snell (who are all non-Indigenous). They not only encouraged her to pursue her idea but also became co-founders of the business and helped her get it off the ground.

They launched Kebaonish two years ago with the goal of bringing harmony and comfort to people everywhere. Because coffee and tea are an integral part of so many people’s days, Barberstock knew they also had an opportunity to do something greater. They could help their consumers— regardless of where they live or who they are— grow closer to Indigenous communities across Canada.

The special teachings within every product

That’s why you’ll find traditional Indigenous teachings emblazoned across the packaging and the official brand pages. “Kebaonish” is Anishinaabemowin for “the warm-hearted feeling of having been away and now returning home.” The brand is also built upon the Anishinaabe principle of Mino-Bimaadiziwin (which roughly translates to “living the good life”) and the Haudenosaunee principle of Ka’nikonhrí:yo (“the good mind”). These are states of being that Barberstock hopes the coffee and tea blends encourage.

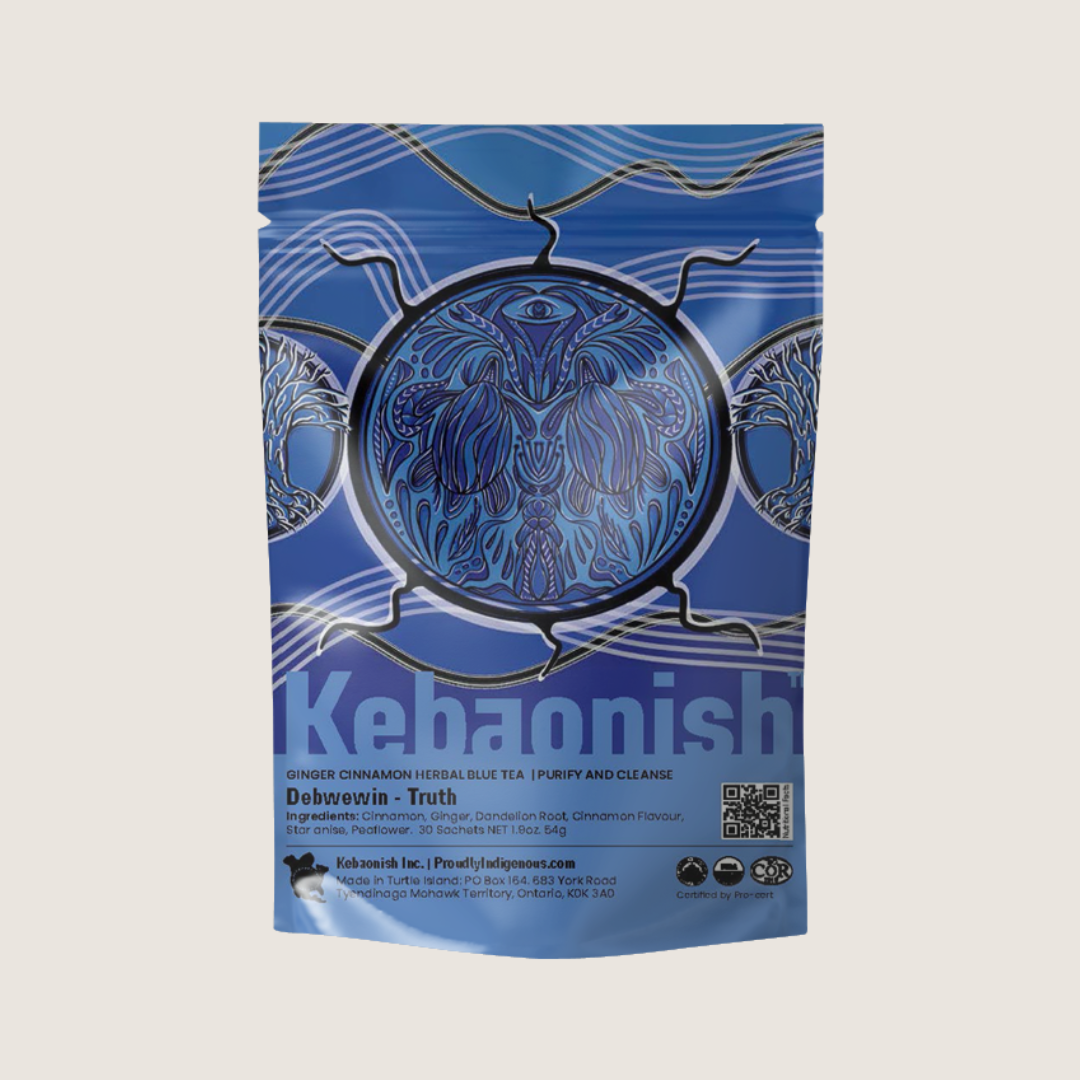

Then there are the products themselves. The brand’s seven teas are inspired by the Anishinaabe Grandfather Teachings, which are guiding principles for life that promote human kindness. The Truth (Debwewin) Tea, for example, is a clean and invigorating blend. With cinnamon, ginger, dandelion root, star anise and butterfly pea flower, it turns a deep blue when steeped. This tea is meant to purify and cleanse.

The Respect (Mnaadendiwin) Tea is anti-inflammatory, calming and slightly sweet and spicy. It features a mixture of ginger, orange peel, turmeric, hibiscus, beet and black pepper with a hazy-pink hue. This principle is rooted in the idea of accepting one another’s differences.

Kebaonish’s four organic coffees are sourced from regions in Central and South America. They embody the messages of the Friendship, Covenant Chain, Dish With One Spoon and Two Row Wampum belt treaties. That includes Friendship (a.k.a. Atenró:sera, a blond-medium roast), Peace (Skén:nen, a dark roast), Respect (Kakwennyenstáhtshera, a medium roast) and Sharing (Sha’teteni’nikonhrò:ten, a medium-dark roast).

“I’m really hoping that people will pick up this coffee and tea and go, ‘Huh? Seven Grandfather Teachings? What are those? What does that mean?’” Barberstock says. “I’m really, really hoping they will look at it, be intrigued and want to learn more—that’s how I feel we can contribute to reconciliation and connection. Being a bridge is really important to me. And we also want to bring more positivity into the world [with these] philosophical and cultural concepts.”

The business model of economic reconciliation

Naturally, the Barberstocks are always thinking about how to stay connected to Indigenous communities too. A portion of profits support Indigenous-language revitalization, cultural preservation and social-impact programs.

On the day of our interview, Rye had delivered a box of their products to a local food-resource centre. But also fundamental to Kebaonish is economic reconciliation. This is the process in which Indigenous entrepreneurs can achieve self-determination, self-sufficiency and business sustainability alongside the Western business model.

This is an idea that has many levels. For Kebaonish, it could involve getting the company to a point where it employs more Indigenous people. It could also mean bringing more Indigenous people into the coffee and tea industry in general. Another possibility is finding a way to work with more Indigenous suppliers.

And if Kebaonish becomes a flourishing business, it could become a model other Indigenous entrepreneurs could look to. Perhaps they could add their own spin to it too, on their path to economic reconciliation.

“By no means are we trying to create a standard approach, but we are trying to demonstrate concepts, ideas and practices that have been beneficial for us—actually celebrate them and share them with others,” Rye says.

“One of the things I find really meaningful is how we can provide our lived and professional experiences to anyone who might be interested in trying to pursue or establish a business opportunity—just to let them know that there are people who are currently doing it so they don’t feel alone.”