It used to be that in order to find a good restaurant with a decent natural wine list in Canada, you had to look long and hard. And if you wanted to buy natural wine in a store? Well, tough luck. But now, natural wine is everywhere.

Restaurants have started praising good farming practices beyond the foods that grace their menus, and you’d be hard-pressed to find a farm-to-table establishment now whose beverage list isn’t populated with natural wines. Wine stores across the country have also had to adapt to the rising demand for natural wines from consumers, fuelled in part by Instagram accounts tracking the latest releases.

While natural wine is gaining in popularity, there is still no steadfast definition for what it really is. Generally speaking, it’s wine made with minimal intervention in the vineyard and in the cellar. Natural winemakers farm grapes organically or biodynamically, forgoing the use of pesticides, herbicides and other chemicals. (Biodynamic agriculture is a holistic type of farming that follows the lunar cycle and views the vineyard as a living organism.) Once they’re ripe, the grapes are typically harvested manually without the use of machinery.

In the cellar, winemakers will leave the grapes to ferment using indigenous yeast, meaning yeast that is naturally present in the air or on the grape skins. They will let the fermentation process run its course without using any additives, except sometimes for a small amount of sulphur right before bottling — around 10 to 35 parts per million. (There has been a lot of contention in natural wine circles regarding the use of sulphites. Purists consider zero-zero wines — wines made with zero additives, including sulphur — to be the truest form of natural wines, while most people will accept the use of sulphur in small doses to help stabilize the wine and avoid mousiness, an off-flavour reminiscent of a mouse cage that is perceived retronasally after the wine has been in the mouth.)

Conventional wines, on the other hand, are often packed with a slew of additives, such as wood chips, sugar, acids and powders, that manipulate the flavours and qualities of the wines to guarantee that they taste the same every time. Unfortunately, consumers are generally not aware of the additives that end up in their glasses because companies are not required to list the ingredients on the bottles.

People often think that all natural wines are funky, cloudy and weird or glou-glou wines (“glug glug” in French), meaning highly drinkable wines that lack structure and character. But natural wine falls on a spectrum. It can be that sparkling high-acidity porch-pounder you drink with your friends or a bold and serious red whose hard edges will benefit from a few years of aging.

To me, natural wine is about more than grape varietals and winemaking techniques. It’s about the people behind the wines I have loved over the years. It’s about winemakers who have chosen to do things the hard way, naturally. People who have resurrected centuries-old traditions and brought back indigenous varietals after they’d been ripped out, all in the name of preserving their cultural heritage and celebrating their regions. When I drink natural wine, I never feel like I am just drinking wine. I feel like I am experiencing a place and time from the perspective of a winemaker whose personality manages to shine through in the glass.

While conventional winemakers can essentially fix any mistake that happened in the vineyard or in the cellar with additives, natural winemakers can’t. That’s why I find natural winemaking so commendable — one small misstep can lead to the loss of revenue from an entire growing season. This is also why natural wine is generally produced in smaller quantities, making the availability of specific bottles quite uncertain. I have picked 10 bottles from different producers, some of whom I have met and befriended over the years. But don’t fret if you can’t find these specific cuvées at your favourite restaurant or wine shop — just ask them if they have anything else from the same producer or if they can recommend something like it. Remember, part of the fun of drinking natural wine lies in the discovery.

Strohmeier, Schilcher Frizzante

Schilcher is a style of rosé wine strictly produced in the Styrian region, where Franz and Christine Strohmeier make wine. This sparkling wine is made from the local Blauer Wildbacher using the traditional méthode champenoise, resulting in a racy summer wine with a sharp minerality.

€19.75, decantalo.com

Château de Béru, Chablis Terroirs de Béru, Chablis, Chardonnay

Winemaker Athénaïs de Béru’s family has owned and operated this historical domaine for more than 400 years. Terroirs de Béru is a beautiful expression of the oyster shell minerality that develops when Chardonnay is grown on the Kimmeridgian soil of Chablis. Athénaïs’ Chablis might be the antithesis of what people expect when they think of natural wine. It’s clean, elegant and bone dry, with tart acidity and notes of Granny Smith apple and lemon zest.

€27, idealwine.com

Weingut Rita & Rudolf Trossen, Pyramide Riesling Pur’us

Rita and Rudolf Trossen have been pioneers of the natural wine movement in the Mosel region of Germany since converting their vineyard to biodynamics in 1978. Their Pur’us line of wines is unfined, unfiltered and made with zero additives, including sulphur. This Riesling is fresh and alive, with a bright acidity, cider-like qualities and notes of citrus and apple.

$36, kingstonwine.com

Jean-Yves Péron, Côtillon des Dames

Jean-Yves Péron planted his roots in schist-covered sloping vineyards in the French alpine region of Savoy, where he produces several cuvées from micro-parcels using local grapes like Jacquère, Altesse and Mondeuse. Côtillon des Dames is a skin-contact wine that is made from Jacquère and has a complex structure that beautifully balances minerality and acidity with aromas of exotic fruits and a hint of honey.

US$59, kingstonwine.com

Radikon, Ribolla Gialla

We can’t talk about the resurgence of orange wine (white wine that’s vinified like a red wine with skin-contact maceration) without mentioning the Radikon family, who helped repopularize the style two decades ago. Available in a one-litre bottle, Sasa Radikon’s Ribolla Gialla (a grape indigenous to Italy’s Friuli region) is deep orange in colour, full-bodied and savoury, with aromas of candied stone fruit and bergamot.

$51.35, saq.com

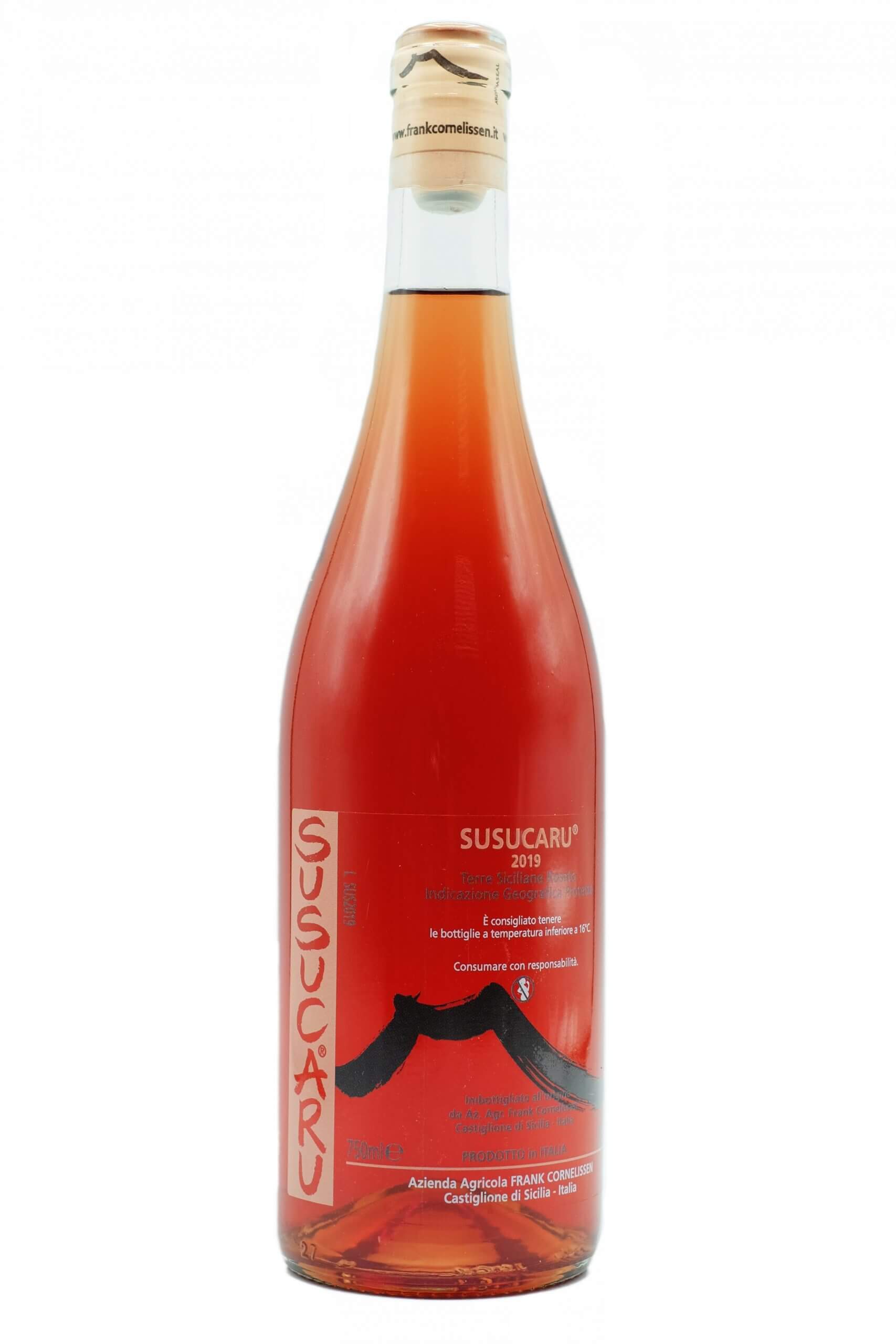

Frank Cornelissen, Susucaru Rosato

Belgian-born Frank Cornelissen crafts some of the world’s most talked about natural wines on the black-sanded slopes of Mount Etna in Sicily. His flagship wine, Susucaru Rosato, is a deep-coloured rosé made from a blend of Malvasia, Moscadella, Insolia and Nerello Mascalese. The result is a bright, light-bodied wine with a volcanic minerality and notes of sour cherry and spices.

$48, ellementwine.ca

L’Imparfait/Hinterland Wine Company, Macération

L’Imparfait is a collaboration between Ontario’s Hinterland Wine Company and Montreal chef David McMillan (formerly of Joe Beef). With an illustrated label by Montreal artist Dan Climan, this macerated blend of Savagnin, Viognier and Gewürztraminer results in a textured and quenchable summer wine with notes of orange peel, honeydew and spices.

$72, hinterlandwine.com