It’s a ritual that spans genres and generations and involves scores of artists, actors, rock stars, athletes and people who are famous for doing nothing at all. When a celebrity reaches a certain level of status, they either create their own spirit brand, buy into somebody else’s or, far more often, simply get paid for the use of their name. A handful of examples has now grown into a horde. A measure of cynicism when approaching such tipples is perfectly justified, but there are enough examples of genuine involvement to give a dram of hope to the jaded.

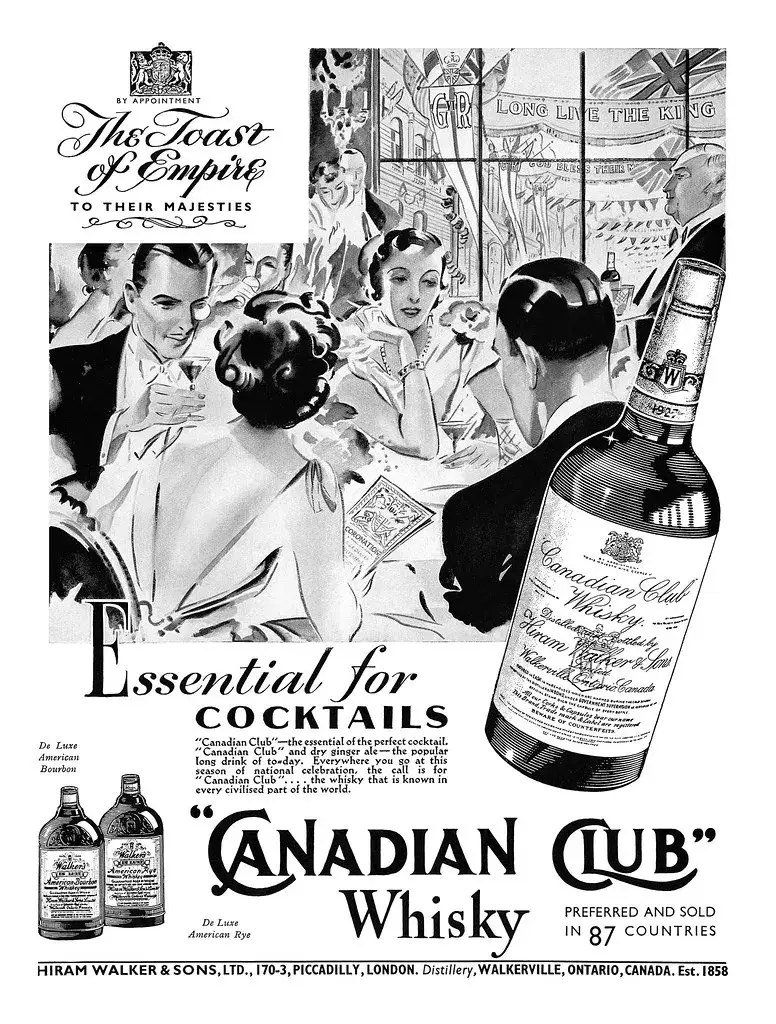

Dedicated stargazers trace the beginning of the celebrity-spirits phenomenon to 1996, when Sammy Hagar, former lead singer of Van Halen, launched his own brand of tequila, Cabo Wabo. But the idea goes back a lot further than that. In 1898, Queen Victoria demonstrated the power of a celebrity endorsement when she granted a royal warrant to Canadian distiller Hiram Walker & Sons. (She had enjoyed an after-dinner Canadian Club whisky – which was produced by Hiram Walker & Sons at the time – and soda for years, on her doctor’s remarkably specific orders.) With the queen’s coat of arms and “by appointment” on the label, CC whisky’s sales went through the roof in every corner of the British empire.

The implication is clear: If a famous person who could drink anything in the world puts their name (or coat of arms) on a bottle, it must be good, right? We would all like to think so, but blatant insincerity on the part of the celeb can ruin the art of the deal. Take Donald Trump, for instance. In 2005, he introduced Trump Vodka in a gaudy golden bottle, but it disappeared from North America by 2011, a victim of poor sales. It seems that customers prefer an authentic connection between the celebrity and the product, and the fact that the president is famously teetotal damaged the credibility of his pitch.

Quality is also an issue. The fan who buys a bottle of expensive booze because he loves the way its spokesperson sings will one day decide to open it. What happens if it tastes awful? The bottle may stay on the bar as a souvenir, but even the most ardent groupie is unlikely to buy another.

So consumers tuck these criteria into their wallets and set off to find a spirit of genuine quality with a bona fide link to a celebrity – someone who’s doing more than just lending their face in return for a payout. With Crystal Head Vodka and Signal Hill Canadian Whisky, Dan Aykroyd has long been ticking all the boxes. The Canadian writer and star of The Blues Brothers, Ghostbusters and Driving Miss Daisy already had a serious presence in the liquor industry as the man who set up an import company to bring Patrón Tequila into Canada in 2005 – a savvy business decision he made after recognizing a gap in the local market.

Not even two years later, he and a friend, artist John Alexander, came up with the idea of selling a different clear spirit in a skull-shaped bottle. “John sketched the smiling skull in two minutes on a bar napkin, and we were in business,” recalls Aykroyd. “[In ancient legend], crystal heads were vessels of light and enlightenment to many Indigenous peoples in North, Central and South America – [they were] used as scrying devices to communicate and see into the future. So I thought there’s only one thing to put inside it, and that’s a pure spirit – a vodka with no additives of any kind.”

It took two years for Italian-glass craftsmen to make enough bottles to launch the brand. “We had 5,000 cases and planned a tour to introduce it across the U.S.,” says Aykroyd. “The first meeting we had was with a big California retail store; he took one look and bought it all without even asking the price.”

It’s not surprising that Aykroyd was at those initial sales meetings. When we meet, 15 years later, he’s just as dedicated to the venture, spending the day in Toronto recording personal video messages to retailers, distributors and even bartenders who have helped build the brand – people he now counts as friends. The world has caught up with the company’s emphasis on purity.

Today’s customers appreciate the fact that Crystal Head is made with no sweeteners or flavourings – something that isn’t impossible to find but is still rare enough that it’s a novelty – and so do the new breed of molecular mixologists, who like working with a pristine canvas when designing a cocktail. “We only have two carbon atoms in our product,” says Aykroyd. “Vodkas with added sugar, glycerine and limonene have a lot more.”

Crystal Head’s success is also down to the excellence of the vodkas themselves. “Original” is a smooth, round Ontario corn spirit with suggestions of citrus and vanilla that come entirely from the grain; “Aurora” uses spirit distilled from wheat grown on a farm in Yorkshire, England, for a sharper, spicier vodka with notes of peppercorn and anise.

The latest expression, “Onyx,” comes in an opaque black skull bottle and is more unorthodox – it’s the only vodka I know that’s made from blue agave, the plant that gives us tequila. It retains some of that juicy green, vegetal, earthy agave taste even though further distillation and seven filtrations have given it the lightweight, pristine texture of vodka. As with all Crystal Head spirits, the last three filtrations are done over Herkimer diamonds – natural semi-precious crystals found in only three places on the planet – to more effectively extract impurities and create a cleaner taste. “To me,” says Aykroyd, “as someone who loves anomalous research and has a background in abrasive psychic studies, they were the perfect touch.”

From the beginning, Aykroyd has steered his company according to his own moral compass. He won’t work with countries that have poor human-rights records, he actively supports diversity and the LGBTQ+ community and he’s environmentally conscious – he eliminated almost all excess packaging, like plastic trays and boxes, over the past five years. He also finds a form of artistic satisfaction in Crystal Head’s success. “It’s like an extension of the entertainment industry,” he says. “It fulfills a sense of creativity in me that people who see me on TV or in the movies can now actually grab a piece of me off the shelf.”

And there’s the nub. That is exactly the sort of two-way communication fans crave when they buy something their idol endorses – the bottle is the symbol of a relationship and of a hope that the celeb in question is in it for more than the money. But cash is always part of the equation. Sammy Hagar set the celebrity-spirit ball rolling when he created Cabo Wabo; he sparked another trend when he sold his remaining share of the company to international drinks giant Gruppo Campari in 2010 for US$11 million. (The group had acquired 80 percent of the tequila brand for a very cool US$80 million a few years earlier.)

Since then, Ryan Reynolds has offloaded his stake in Aviation Gin for US$610 million, 50 Cent sold his stake in Effen Vodka for US$60 million and George Clooney and Rande Gerber handed over Casamigos tequila to liquor titan Diageo for US$1 billion.

How are their followers to react? Do they feel betrayed or are they open-mouthed with admiration? Once again, Sammy Hagar has figured out how to make it work. Now 76, he has simply started over, getting back on the road with Cabo Wabo’s original master distiller, Juan Eduardo Nuñez, and restaurateur/TV personality Guy Fieri to give his loyal supporters a new line of good, honest tequilas, this time under the label Santo.

There will always be critics who disparage the whole idea of celebrity spirits, but when the product is good and the involvement authentic, it’s a win-win-win situation. The liquor industry loves it – suddenly a brand acquires glamour, stands out from the competition and brings in an army of new customers. The stars get to add “connoisseur” to their resumé, scratch a creative itch and strengthen ties with their followers. As for the fans, it’s the next best thing to sitting down with their idol and having them pour a drink.